Since the new millennium, South Korea has consistently ranked as one of the most connected countries in the world, with over 96 percent having daily internet access. Much of this access has been through smartphones, with a staggering 95 percent of adults owning one.

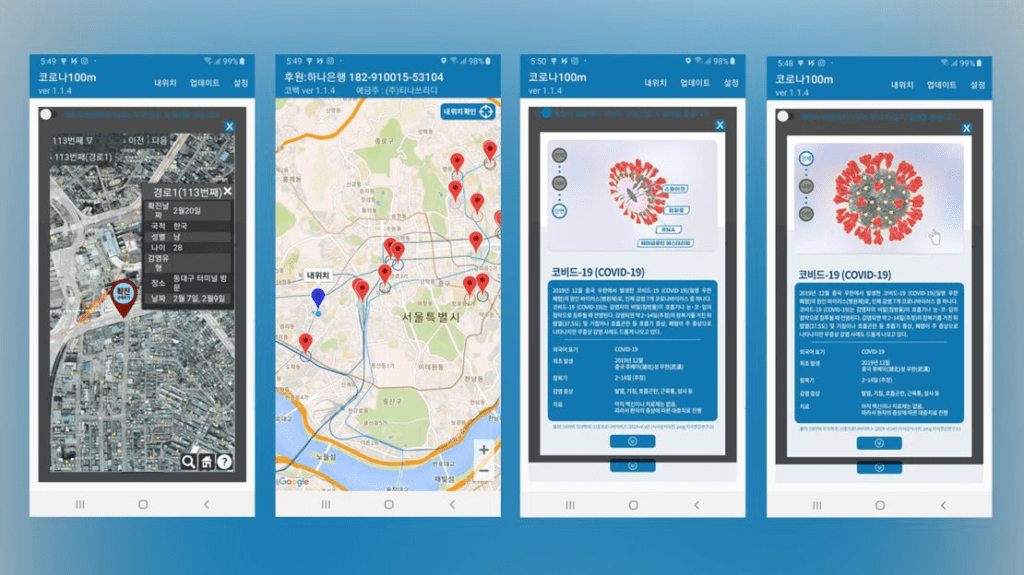

This connectivity has, over the years, precipitated policies allowing law enforcement officers to collect mobile phone locations in pursuit of criminals. Amid the outbreak, this information has been repurposed to retroactively track both COVID-19 patients and suspected patients. Though its rigorous contact-tracing program has proven successful in preventing cases of disease, it has also been criticized for its possible misuse in other cases of digital tracking.

South Korea, renowned for its advanced digital infrastructure, is increasingly under scrutiny for its expansive internet censorship practices. The nation’s approach to online regulation, particularly concerning national security and social norms, has drawn criticism from global observers and digital rights organizations.

From 1995 to 2002, the government of South Korea passed the Telecommunications Business Act (TBA), the first internet censorship law in the world.

| Key Legislation & Online Censorship Impacts |

|---|

| Law/Policy | Key Points | Implications |

| Telecommunications Business Act | – Gov’t regulates telecoms – Limits foreign ownership – KCC oversight | Can enable state control of online access and content |

| SNI Snooping (2019) | – Used to block HTTPS sites – Public backlash & 230k+ petition signatures | Raised alarms over privacy and press freedom online |

| Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC Appointments) | – Most members appointed by president – Ruling party holds majority | Questions around neutrality and potential political bias in censorship decisions |

| Cyber Defamation Law | – Criminalizes online defamation, even if statements are true. – Up to 7 years imprisonment or fines up to 50 million won. | Used to intimidate journalists and critics. Encourages self-censorship online. |

The TBA was the first internet censorship law in the world, and it led to the establishment of the Internet Communications Ethics Committee (ICEC), tasked with monitoring online content and recommending the removal of material considered unlawful.

In the initial eight months of 1996 alone, the ICEC removed approximately 220,000 messages from internet platforms. These messages ranged from criticism of celebrities, political sympathies with North Korea, and commentary on politicians.

Subsequent revisions to the TBA between 2002 and 2008 expanded the ICEC’s capabilities, allowing for more sophisticated internet policing. This period saw increased efforts to curb online speech, partly in response to incidents of cyberbullying and related suicides. In 2007, reports indicated over 200,000 cases of cyberbullying, prompting further governmental action.

A significant aspect of South Korea’s online regulation is its “cyber defamation law,” (사이버 명예훼손죄) which empowers law enforcement agencies to act against online comments deemed “hateful,” even in the absence of complaints from victims.

Public anger over the 2008 suicide of celebrity Choi Jin-sil led to a legislative push for stronger legislation against cyberbullying, including the adoption of a real name system. This has led to prosecutions and sentences for individuals based on their online expressions, raising concerns about freedom of speech and expression.

The election of President Lee Myung-bak in 2008 marked a significant escalation in online censorship. The government established the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC), replacing the ICEC as the primary regulatory body. Under those regulations, websites with over 100,000 daily visitors were required to implement real-name verification systems, mandating users to register with their real names and social security numbers.

This is true for most sign-up systems in Korea; actions like trying to read a webtoon or buying your friend a cake as a Kakao gift require i-Pins or social security numbers.

Additionally, the KCSC was authorized to suspend or delete web postings for up to 30 days upon receiving complaints, leading to the removal of approximately 23,000 webpages and the blocking of another 63,000 in 2013 alone.

In 2019, the government’s decision to employ Server Name Indication (SNI) snooping to censor HTTPS websites sparked significant public outcry. Over 230,000 citizens signed a petition opposing the measure, but the government proceeded, asserting the independence of the KCSC from its operations. However, investigations revealed that most KCSC members were presidential appointees, casting doubt on the commission’s impartiality.

International organizations have expressed concern over South Korea’s internet censorship practices. The OpenNet Initiative categorized the country’s censorship as “pervasive” in conflict/security areas and “selective” in social contexts. Reporters Without Borders included South Korea in its list of countries “Under Surveillance” in 2011 and 2012, highlighting the government’s intensified efforts to control online content. Freedom House has also reported ongoing issues related to online harassment and restrictions on freedom of expression.

As South Korea continues to navigate the challenges of digital governance, the balance between national security, social norms, and individual freedoms remains a contentious and closely watched issue both domestically and internationally.